Io sono Li (Shun Li and the poet)

by Andrea Segre (director and writer)

Italy-France, 2011, 1h36

with Zhao Tao (Shun Li), Rade Sherbedgia (Bepi), Marco Paolini (Coppe), Roberto Citran (l'Avocat), Giuseppe Battiston (Devis)

Critical review by the cultural center Les Grignoux (Liège, Belgium)

Since 2007, the European Parliament LUX FILM PRIZE casts an annual spotlight on films that go to the heart of European public debate. The Parliament believes that cinema, a mass cultural medium, can be an ideal vehicle for debate and reflection on Europe and its future.

The films selected for the LUX FILM PRIZE competition help to air different views on some of the main social and political issues of the day and, as such, contribute to building a stronger European identity. They help celebrate the universal reach of European values, illustrate the diversity of European traditions and shed light on the process of European integration.

Three great films competed for the LUX Prize 2012: Csak a szél (Just the Wind) by Bence Fliegauf , Io Sono Li (Shun Li and the Poet) by Andrea Segre and Tabu by Miguel Gomes

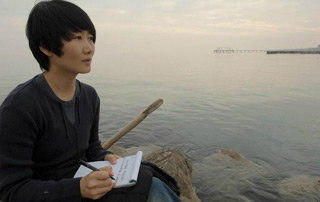

Shun Li, a young Chinese woman who works in a textile factory on the outskirts of Rome, is one day transferred to Chioggia, near Venice, to work as a waitress in a café frequented by a number of elderly fishermen, including Bepi (known as 'the poet'), a Yugoslav immigrant who arrived 30 years previously. Bepi and Shun Li strike up a friendship despite the disapproval of the local Italian and Chinese communities

Shun Li, a young Chinese woman who works in a textile factory on the outskirts of Rome, is one day transferred to Chioggia, near Venice, to work as a waitress in a café frequented by a number of elderly fishermen, including Bepi (known as 'the poet'), a Yugoslav immigrant who arrived 30 years previously. Bepi and Shun Li strike up a friendship despite the disapproval of the local Italian and Chinese communities

'Shun Li and the Poet', the first full-length drama by documentary film-maker Andrea Segre, is a restrained and sensitive depiction of an encounter between different cultures.

Shun Li, who has come to Italy to work in a textile factory on the outskirts of Rome before being sent to Chioggia, near Venice, to work as a café waitress, is in the hands of a shadowy Chinese (mafia?) organisation, which has paid for her flight and residence permit. She is required to repay the money by working for the organisation for an indeterminate period. The fact that she has left a young son in China who cannot come out to join her until her debt has been fully repaid makes her even more vulnerable.

Shun Li, who has come to Italy to work in a textile factory on the outskirts of Rome before being sent to Chioggia, near Venice, to work as a café waitress, is in the hands of a shadowy Chinese (mafia?) organisation, which has paid for her flight and residence permit. She is required to repay the money by working for the organisation for an indeterminate period. The fact that she has left a young son in China who cannot come out to join her until her debt has been fully repaid makes her even more vulnerable.

In Chioggia, where she is employed as a café waitress, she comes into close contact with the Italian populace, most of them elderly fishermen. Shun Li has probably never before encountered Italians at such close quarters. A small group of friends, Bepi, Coppe, 'the lawyer' and Moustache regularly go to the Osteria Paradiso to drink, talk or play cards. They take the new waitress under their wing, explaining to her what the orders mean and how to serve them, while gently making fun of the fact that she neither understands nor speaks Italian very well. Their attitude towards this solitary young foreign woman is one shown by the stronger to the weaker, a mixture of gruff kindliness protectiveness, indulgence and good natured teasing, unlike two younger clients, Devis and his friend, who treat her with undisguised contempt.

As time goes on, the fishermen become friendlier, sample Chinese cooking with varying degrees of appreciation and invite Li to join them for a drink to celebrate Coppe's retirement. However, it is Bepi, the Yugoslav immigrant of 30 years standing, who establishes a genuine rapport with Li on discovering that her father was a fisherman like him. She shows him photographs of her father at work and of her son, whom she misses and whom she hopes will soon be able to join her. She also mentions the traditional poetry festival, to which she is particularly attached. Bepi, who occasionally turns his hand to poetry himself, is intrigued by the Chinese tradition of floating lanterns on the river to commemorate the celebrated poet Qu Yuan. Li and Bepi are also political soul mates – Bepi having known Communism under Tito in Yugoslavia. A friendship slowly burgeons between them, both of them alone and in a foreign country. Bepi offers Li the use of his telephone to call her son in China and invites her to his fishermen's hut perched on stilts in the lagoon. Witnessing her sadness at not knowing when she will see her son again, he takes her in his arms.

As time goes on, the fishermen become friendlier, sample Chinese cooking with varying degrees of appreciation and invite Li to join them for a drink to celebrate Coppe's retirement. However, it is Bepi, the Yugoslav immigrant of 30 years standing, who establishes a genuine rapport with Li on discovering that her father was a fisherman like him. She shows him photographs of her father at work and of her son, whom she misses and whom she hopes will soon be able to join her. She also mentions the traditional poetry festival, to which she is particularly attached. Bepi, who occasionally turns his hand to poetry himself, is intrigued by the Chinese tradition of floating lanterns on the river to commemorate the celebrated poet Qu Yuan. Li and Bepi are also political soul mates – Bepi having known Communism under Tito in Yugoslavia. A friendship slowly burgeons between them, both of them alone and in a foreign country. Bepi offers Li the use of his telephone to call her son in China and invites her to his fishermen's hut perched on stilts in the lagoon. Witnessing her sadness at not knowing when she will see her son again, he takes her in his arms.

That is all it takes to upset the balance and destroy Li's acceptance by the Italian community. Rumours begin to run wild that she is having an affair with Bepi, that she is in the pay of the Chinese mafia, which is sending women to seduce and marry elderly Italians in order appropriate their estate. The Chinese are everywhere. It's an invasion, a new form of imperialism. The Chinese also disapprove of the friendship between Li and Bepi because of these very rumours, accusing Li of giving the Chinese a bad name in Italy and forbidding her from speaking to Bepi except to wait on him in the café. Under pressure from their respective communities, they are unceremoniously forced apart.

In this way, an inoffensive young woman who is vulnerable, foreign and alone, unable even to speak the language properly, suddenly becomes a threat to Italian society. The film is a remarkable depiction of crossing a line and thus changing the way we look at each other. The burgeoning friendship between Li and Bepi is suddenly no longer acceptable, since it is seen as threatening to exclude all others and remove Bepi from the group to which he belongs. The individuals themselves are also seen in a different way. Li is no longer regarded as an insignificant waitress but as a symbol or forerunner of imperialist China. Bepi, who is otherwise never allowed to forget his origins, suddenly comes to represent wealthy Italian society, despite the fact he owns nothing more than a scooter and a fisherman's hut!

In this way, an inoffensive young woman who is vulnerable, foreign and alone, unable even to speak the language properly, suddenly becomes a threat to Italian society. The film is a remarkable depiction of crossing a line and thus changing the way we look at each other. The burgeoning friendship between Li and Bepi is suddenly no longer acceptable, since it is seen as threatening to exclude all others and remove Bepi from the group to which he belongs. The individuals themselves are also seen in a different way. Li is no longer regarded as an insignificant waitress but as a symbol or forerunner of imperialist China. Bepi, who is otherwise never allowed to forget his origins, suddenly comes to represent wealthy Italian society, despite the fact he owns nothing more than a scooter and a fisherman's hut!

While the audience, who probably identify with Li and Bepi, might consider this unfair, it is simply an example of the stereotyping, of which we are all at some time or another guilty. Faced with what (sometimes wrongly) appears to be a threat [1] – in this case the possibility of Li marrying Bepi for his property – individuals become swallowed up in the prejudices which typecast their communities, in this case the Chinese, who are perceived to be invading the world and out to rob us of everything we have. Once the rumours have begun to spread, Devis prevents Bepi from entering the café with the remark 'Watch out for the Chinese mafia', as if Li alone represented a danger.

The press [2] regularly refers to Chinese investment abroad. Vigorous Chinese growth rates cannot fail to impress nations lagging behind. Hence what comes to define a country or community is suddenly applied to individuals also, irrespective of their own qualities and faults. A moment of tenderness between Bepi and Li is interpreted as a relationship and possibly a future marriage, as if Li herself personified the fantasies and fears of each community with regard to the other.

'Shun Li and the Poet' could thus be interpreted as a warning against stereotyping, which, in certain circumstances, leads us to consider people not as individuals but as representatives of a community or culture with all its defects or presumed intentions.

The end of the friendship between Li and Bepi, which also reflects the disruption of relations between the Italians and Chinese on the one hand and between the native Italians and Bepi on the other, could be interpreted in various ways. It might be argued that their rapprochement threatens to undermine the little community of Chioggia. Indeed, Italian society, as depicted in the film, appears to be based on all kinds of oppositions and extremes, which nevertheless balance each other out establishing a status quo. By narrowing down such differences, Bepi and Li alter the equation, thereby threatening the social equilibrium.

The end of the friendship between Li and Bepi, which also reflects the disruption of relations between the Italians and Chinese on the one hand and between the native Italians and Bepi on the other, could be interpreted in various ways. It might be argued that their rapprochement threatens to undermine the little community of Chioggia. Indeed, Italian society, as depicted in the film, appears to be based on all kinds of oppositions and extremes, which nevertheless balance each other out establishing a status quo. By narrowing down such differences, Bepi and Li alter the equation, thereby threatening the social equilibrium.

The film opens with a depiction of a traditional ceremony in honour of the poet Qu Yuan. It appears at different moments during the film and, while the concept of yin and yang is never explicitly mentioned, it fits in naturally with certain scenes. In a letter to her son, Li compares the sea, which in Italian is masculine – never still and rocked by the winds and waves – to the calm and mystery of the lagoon, which is feminine. The two concepts represent two aspects of the same thing. 'Shun Li and the Poet' can therefore be seen in terms of contrast, which is by no means lacking in this film.

There is the contrast between the Chinese and Italians of course, with their different languages, cultures and cuisine. This does not however prevent them from coexisting amicably and the market scene where a Chinese is seen haggling over prawns can be interpreted as representing the possibility of getting along together despite differences.

There is the contrast between the Chinese and Italians of course, with their different languages, cultures and cuisine. This does not however prevent them from coexisting amicably and the market scene where a Chinese is seen haggling over prawns can be interpreted as representing the possibility of getting along together despite differences.

There is also the contrast between men and women. The patrons of the café are all male and Li is alone behind the bar. The only woman who enters the café (and promptly leaves again) is Devis' furious wife, who has come to leave her son with his father so that she can take their younger child, who is sick, to the doctor. While we see the men working on the fishing boat, women are much less in evidence. It would appear that the two live in parallel worlds which never really meet.

There is also a contrast between young and old. While the group of elderly fishermen is relatively homogeneous, they are not the same as Devis and his friend, neither of whom show Li the slightest courtesy, engaging in dubious activities and obviously never short of cash. Bepi himself is at odds with his own son, who cannot comprehend his outdated lifestyle (no cars, no lifts and no microwaves) and who regards Bepi as older than he really is. He would like his father to live closer to his own home in Mestre in case 'anything should happen', to which Bepi retorts, 'I am alone, not dead!'.

The young and the old thus have different attitudes to life, the young adopting a modern, no-time-to-waste and materialist outlook, while the old remain attached to the values of tradition, simplicity and friendship (at the beginning of the film, set among the Chinese community, the same contrast can be observed between respect for tradition — the celebration of poetry by Shun Li — and the disrespect shown by the gamblers…)

The young and the old thus have different attitudes to life, the young adopting a modern, no-time-to-waste and materialist outlook, while the old remain attached to the values of tradition, simplicity and friendship (at the beginning of the film, set among the Chinese community, the same contrast can be observed between respect for tradition — the celebration of poetry by Shun Li — and the disrespect shown by the gamblers…)

There is also a contrast between work and rest. The work of the fishermen requires strength and skill. Devis does not appear to work, spends his time racing speedboats and boasts of being able to earn a great deal of money quickly and effortlessly. When Coppe's friends are celebrating his retirement, they invite one of the Chinese to join them but he declines because he has work to do: 'Working, always working,' the fishermen reply. The theme of work and inactivity is omnipresent in the film and could even be generalised in terms of the contrast between an ageing Europe, which appears to be entering period of repose (not to say recession) and China with its vigorous growth and boundless energy.

Li and Bepi narrow down these differences in the form of a friendship between an (assimilated) Italian and a Chinese, a man and a woman, an older and younger person, a pensioner and a worker. Perhaps the juxtaposition of these contrasts is regarded as a threat to the social order because it overturns too many conventions.

Andrea Segre's style is extremely limpid and the film contains scenes presented with great economy of style in which the audience learns a great deal very quickly. The opening of the film, for example, gives a full picture of Li's situation even before the title appears on the screen and presents the homage to the Chinese poet which recurs regularly throughout the film.

This reference to the Chinese poet Qu Yuan is followed by first images of the film with small candles being placed on the water by two young Asian women, thereby giving the film a traditional Chinese flavour. However, this scene and the feelings (of peace, contemplation, mystery ...) which it inspires are brutally interrupted by a man abruptly turning on the light (we discover that the scene is set in a bathroom and that the water is in the bath) and displaying utter contempt for the ceremony, declaring, 'We are in Italy now' and proceeding to urinate in front of the two women, making it abundantly clear how much he despises their ancient beliefs. The audience is put in the picture immediately. This is a Chinese community in Italy and an abyss separates the young women attached to tradition and the men playing Mah-jong in a nearby room, drinking and swearing. We then follow one of the two women, Shun Li, who works in a textile factory. She is summoned by the foreman and informed that she will be leaving for Chioggia, near Venice. Shun Li has no choice. Her flight and residence permit have been paid for and she is required to reimburse the full amount. She agrees, returns home and begins in her mind to compose a letter to her son back in China. She misses him but they will soon be reunited. All her work is with this aim in mind - to pay for her son's journey. All this is said even before the title of the film appears on the screen.

This reference to the Chinese poet Qu Yuan is followed by first images of the film with small candles being placed on the water by two young Asian women, thereby giving the film a traditional Chinese flavour. However, this scene and the feelings (of peace, contemplation, mystery ...) which it inspires are brutally interrupted by a man abruptly turning on the light (we discover that the scene is set in a bathroom and that the water is in the bath) and displaying utter contempt for the ceremony, declaring, 'We are in Italy now' and proceeding to urinate in front of the two women, making it abundantly clear how much he despises their ancient beliefs. The audience is put in the picture immediately. This is a Chinese community in Italy and an abyss separates the young women attached to tradition and the men playing Mah-jong in a nearby room, drinking and swearing. We then follow one of the two women, Shun Li, who works in a textile factory. She is summoned by the foreman and informed that she will be leaving for Chioggia, near Venice. Shun Li has no choice. Her flight and residence permit have been paid for and she is required to reimburse the full amount. She agrees, returns home and begins in her mind to compose a letter to her son back in China. She misses him but they will soon be reunited. All her work is with this aim in mind - to pay for her son's journey. All this is said even before the title of the film appears on the screen.

Now that the scene has been set, we know that Shun Li is in the hands of a shadowy Chinese organisation to which she owes money and that her son cannot join her until she has paid off her debt. She is attached to Chinese traditions which it is difficult for her to follow in Italy, making it easy to imagine her feelings of isolation and loneliness.

However if the film is extremely explicit in certain scenes such as the one we have just mentioned, there is also ambiguity and mystery. For example, there are questions regarding the Chinese organisation to which Li owes money. Li does not know when her debt will be repaid, is awaiting mysterious news which will arrive at some indeterminate time in the future, must obey the organisation, which takes on different forms from a textile factory to Rome to a small café in Chioggia, and is being threatened that she will have to pay her debt from the beginning if she misbehaves. All this implies a dubious, illegal mafia-style organisation. On the other hand, it does not appear to crush individuals as it would if it were totally evil. The conditions of work in the textile factory appear to be acceptable (the women working there are not placed under any pressure, the noise of the machines is not deafening), the foreman is quite amicable and Li's 'transfer' appears to be by way of promotion for the quality of her work. She is allowed to travel unaccompanied from Rome to Chioggia and, while her accommodation is not particularly comfortable, neither is it squalid. Her work in the café is also perfectly ordinary and does not appear to involve ruthless exploitation (although she does have to wait a long time for her days off). Finally, the organisation is willing to acknowledge that someone else has paid off Li's debt and will allow her son to join her earlier than scheduled.

However if the film is extremely explicit in certain scenes such as the one we have just mentioned, there is also ambiguity and mystery. For example, there are questions regarding the Chinese organisation to which Li owes money. Li does not know when her debt will be repaid, is awaiting mysterious news which will arrive at some indeterminate time in the future, must obey the organisation, which takes on different forms from a textile factory to Rome to a small café in Chioggia, and is being threatened that she will have to pay her debt from the beginning if she misbehaves. All this implies a dubious, illegal mafia-style organisation. On the other hand, it does not appear to crush individuals as it would if it were totally evil. The conditions of work in the textile factory appear to be acceptable (the women working there are not placed under any pressure, the noise of the machines is not deafening), the foreman is quite amicable and Li's 'transfer' appears to be by way of promotion for the quality of her work. She is allowed to travel unaccompanied from Rome to Chioggia and, while her accommodation is not particularly comfortable, neither is it squalid. Her work in the café is also perfectly ordinary and does not appear to involve ruthless exploitation (although she does have to wait a long time for her days off). Finally, the organisation is willing to acknowledge that someone else has paid off Li's debt and will allow her son to join her earlier than scheduled.

It is also very difficult to pin down certain characters such as Devis, whose unspecified activities appear to be as dubious as those of the Chinese organisation.

Similarly, the nature of the relationship between Li and Bepi is unclear. Is it love or friendship? What is each of them looking for? The other characters immediately conclude that Bepi is seeking a sexual relationship and that Li is after his money. The audience, who can see that this is a massive oversimplification, is nevertheless left equally in the dark.

Finally, the film presents another great unsolved mystery. Lian, Li's roommate, does not appear to work and seems to spend her time sitting on the bed reading magazines. However, she mysteriously appears in other settings, particularly in the street after nightfall. What is she doing? Is she prostituting herself for the Chinese organisation [3]? If so, we may imagine that Lian, unlike Li, may be forced to work under soul- destroying conditions which could end up destroying her. When Li mentions her friendship with Bepi, Lian advises caution. 'The Italians are our customers' she says, which could have a double meaning if we assume that she is a prostitute. Finally, what is the meaning of Lian's final gesture? Perhaps, feeling herself being destroyed by the mafia, which is obliging her to prostitute herself, she decides to sacrifice herself for Li. Perhaps she is setting aside money from her clients [4] to give to Li before disappearing without a trace.

Finally, the film presents another great unsolved mystery. Lian, Li's roommate, does not appear to work and seems to spend her time sitting on the bed reading magazines. However, she mysteriously appears in other settings, particularly in the street after nightfall. What is she doing? Is she prostituting herself for the Chinese organisation [3]? If so, we may imagine that Lian, unlike Li, may be forced to work under soul- destroying conditions which could end up destroying her. When Li mentions her friendship with Bepi, Lian advises caution. 'The Italians are our customers' she says, which could have a double meaning if we assume that she is a prostitute. Finally, what is the meaning of Lian's final gesture? Perhaps, feeling herself being destroyed by the mafia, which is obliging her to prostitute herself, she decides to sacrifice herself for Li. Perhaps she is setting aside money from her clients [4] to give to Li before disappearing without a trace.

Thus, while everything seems very clear at the beginning, the film gradually becomes deeper, more troubled and more ambiguous than it at first appears. With regard to both events and individuals, it requires us to abandon our first impressions, which could turn out to be inaccurate, ill-considered and oversimplified.

5. Issues raised by the film for discussionWhy do you think the Italians cannot accept the friendship between Li and Bepi? How does it upset them? Do you agree with the interpretation put forward here that it is sign of Chinese imperialism? Do you have any other theories? Why do you think that the Chinese cannot accept the friendship between Li and Bepi? Is it simply that, as they say, it will give the Chinese a bad name or could there be some other hidden motives? Why is Li sent to another town when she appears to be willing to obey her Chinese masters and end her friendship with Bepi? Do you think that this story could have taken place in another setting (your town or country for example) with people of other origins? How would the story have been different? The film has a bittersweet ending since, on the one hand, Li is reunited with her son but, on the other, Lian has disappeared and Bepi is dead. Is the dominant tone one of happiness or sadness? What do you think is the most likely explanation for Lian's disappearance and Bepi's death? |

1. 'The lawyer' observes, 'Things are getting dangerous'.

2. For example in September 2012 Le Monde diplomatique published an article by Michael T. Klare entitled 'Is China imperialist?'

3. Devis boasts to his friend that he has used the services of an expensive, high-class prostitute, which implies that prostitution is a fact of life in Chioggia.

4. In her first letter to her son, Li writes: 'When the chief asks me to sew 30 shirts a day, I sew 10 more for you'. Lian may be adopting the same system, thereby earning more for Li's son.