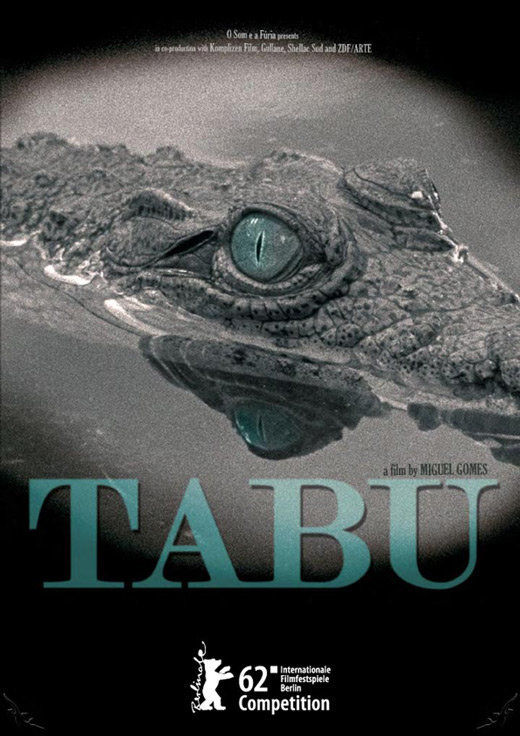

Tabu

a film by Miguel Gomes

Portugal. 2012. 2 hours

Featuring Teresa Madruga (Pilar), Laura Soveral (old Aurora), Ana Moreira (young Aurora), Henrique Espírito Santo (old Gian Luca Ventura), Carloto Cotta (young Ventura), Isabel Cardoso (Santa), Manuel Mesquita (Mário)

Alfred-Bauer Prize, Berlin International Film Festival 2012

The first part of Tabu, entitled 'Paradise lost' (Paraíso perdido) takes place in modern-day Lisbon and concerns Pilar, a 50-year-old member of the Taizé Christian community, who devotes her time to others and to various good causes. In particular, she occasionally looks after her elderly neighbour, Aurora, who suffers from senile dementia and believes that she is being persecuted by her black servant, Santa, and considers herself abandoned by her daughter. However, Pilar's devotion does not seem to evoke any real response either from the people around her or from this elderly woman who retreats into her obsessions.

In particular, she occasionally looks after her elderly neighbour, Aurora, who suffers from senile dementia and believes that she is being persecuted by her black servant, Santa, and considers herself abandoned by her daughter. However, Pilar's devotion does not seem to evoke any real response either from the people around her or from this elderly woman who retreats into her obsessions.

Aurora's unexpected death then brings out a deeply buried past, in the second part of the film: 'Paradise' (Paraíso). Gian Luca Ventura, a long-lost lover of Aurora, reveals to Pilar and Santa the old woman's hidden past, a story of a secret love that brought them together in Africa in a Portuguese colony in the grip of the initial unrest of the fight for independence. Characterised by remembrance, the second part of the film abandons the initial realism in favour of a much more detached, almost dreamlike, aesthetic.

Most viewers will certainly notice the aesthetic and cinematographic originality of Tabu, which, notably, is filmed in black and white in an unusual aspect ratio, but they may also question its exact significance: the film is characterised in particular by a break in the narrative which takes us from the present to the past, while shifting our interest from one character to another: from Pilar, the religious woman from Lisbon who is devoted to others, to Aurora, a probably senile old woman whose unexpected and romantic story will be revealed to us by her former lover.

These two very different characters seem linked somewhat tenuously even though the character of Aurora appears at different ages. While everyone is clearly free to interpret this diptych and Tabu's other aesthetic features as they see fit, some areas for consideration can nonetheless be suggested to aid discussion. There are thus three possible main areas for discussion.

A series of analogies and contrasts can easily be spotted between the two parts of the film, which each feature a female central character (Pilar/Aurora), one who is old, the other in her youth, one guided by her love for others, the other controlled by a much more personal, if not selfish, passion. The romanticism of the colonial 'Paradise' of the past also contrasts with the mundane realism of modern-day Lisbon.

What best defines the first part of the film is undoubtedly its low-key atmosphere and the feeling of an unending wait. For example, one of the first scenes shows Pilar coming to welcome Maya, a young Polish woman, at the airport, but the young woman that she meets says she is only Maya's friend and that Maya was unable to come to Lisbon. It is immediately clear, however, that this is a lie and that the young woman does not want to stay with this older woman - no doubt preferring to stay with friends of her own age. Pilar then waits, seemingly without any anger or bitterness.

Similarly, in the next sequence, she listens patiently and meekly as elderly Aurora explains a dream to her about hairy monkeys and a train ticket inspector whose ticket machine appears to be a slot machine. The dream is supposed to explain why Aurora has lost all her money in the casino. Next we see Pilar taking part in a demonstration against the UN's passivity with regard to a genocide that is not explained to the viewer. Pilar is full of goodwill, driven by a sincere faith and is devoted to others, but she seems to face an immobile world that does not care about or is indifferent to her presence and her action.

Similarly, in the next sequence, she listens patiently and meekly as elderly Aurora explains a dream to her about hairy monkeys and a train ticket inspector whose ticket machine appears to be a slot machine. The dream is supposed to explain why Aurora has lost all her money in the casino. Next we see Pilar taking part in a demonstration against the UN's passivity with regard to a genocide that is not explained to the viewer. Pilar is full of goodwill, driven by a sincere faith and is devoted to others, but she seems to face an immobile world that does not care about or is indifferent to her presence and her action.

Conversely, the only person that seems to be interested in her, a painter friend, only receives little attention from her, attention that is sometimes even embarrassed when she hangs a painting he gives her before taking it down because she does not actually like it. However, another scene is even more revealing in this regard since we see both of them at the cinema, him asleep and her crying silently while listening to the music on-screen, a Portuguese version of 'Be My Baby' by The Ronettes (1963).

On leaving the cinema, her old friend wishes her happy new year and makes an awkward and embarrassed declaration of love, before giving her a new painting! The tone of this scene wavers between the emotional and the ridiculous, even though it is clear to the viewer that this somewhat ridiculously expressed love is not shared by Pilar. All the scenes in the first part are steeped in the same weighty atmosphere, a reflection of an apparently joyless existence which seems literally to be on hold.

There is then a gripping contrast with the passion of the second part, which is characterised by its rages, its brutal twists and its tragic epilogue. However, there appears to be a series of sometimes tenuous links between these two disjointed chapters.

It should be remembered that the film begins with a rather strange sequence: It shows a Portuguese explorer in the 19th century 'in the heart of the dark continent', driven not by the taste for adventure or a greater will, that of the king or god, but by a gnawing heartache, caused by the death of a woman he loved, before he dies himself, devoured by a crocodile that is now as melancholy as its victim. This prologue, in which we can detect a hint of irony, is revealed to be a film that Pilar is watching, alone in a cinema. This tragic love story, which is set in a colonial context, thus immediately seems steeped in the cinematographic fiction into which Pilar seems willingly to immerse herself - we see her with her painter friend at another screening which is deeply moving for her. Is this a way for the director, Miguel Gomes, to suggest that romantic passion is merely a dream or a fantasy, or even imaginary compensation, for this character who is stuck in a lacklustre mundane life?

This prologue, in which we can detect a hint of irony, is revealed to be a film that Pilar is watching, alone in a cinema. This tragic love story, which is set in a colonial context, thus immediately seems steeped in the cinematographic fiction into which Pilar seems willingly to immerse herself - we see her with her painter friend at another screening which is deeply moving for her. Is this a way for the director, Miguel Gomes, to suggest that romantic passion is merely a dream or a fantasy, or even imaginary compensation, for this character who is stuck in a lacklustre mundane life?

This romantic theme then seems to fade even though it is recalled incidentally by Aurora as she describes her dream after her disappointment at the casino. She recalls the friend, the unfaithful wife of the man who is as hairy as a 'monkey', who claimed to be, as the conventional phrase goes: 'lucky at cards, unlucky in love'. However, this incidental reference in a rather absurd dream is easily overlooked by viewers, as, no doubt, is the song heard in the cinema that Pilar listens to with tears in her eyes. It is, however, the same piece - 'Be My Baby' - that is played in the second part of the film by Gian Luca with his orchestra when he has to be separated from his mistress for several months. At that point, the editing emphasises the emotion of the two lovers, Aurora listening to that song on the radio, shaking with great sobs, then in the next shot Gian Luca sitting at his drum kit, his face literally twisted in pain. Love, whether it is actually experienced or only felt in an imaginary way by Pilar in the cinema, thus appears to be an essential vector of intense emotion for the individuals on screen in either part of the film.

More formally, it can be noted that the two parts of the film are cut into clear time sequences, the first in days (from 28 December 2010 to 3 January 2011), and the second in months (from October to August without the year being specified). This insistence on the differentiated passage of time can probably be understood as a way of emphasising the contrast between the intensity of passion that makes time pass more quickly and a mundane life that, conversely, seems to slow it down if not bring it to a standstill.

Consequently, we might wonder whether the titles of the two parts should be taken literally: 'Paradise lost/Paradise'? At the heart of a rigid, disappointing, inconclusive present, lies the memory of a stronger, more intense, more passionate past. Thus the words of Aurora who, during her last hospitalisation, talks about a crocodile that would hide at Gian Luca Ventura's house, seem just as absurd to Pilar (who replies to her only that she should rest) as to the viewers, but they are soon revealed to be perfectly sensible since they refer to a past that is certainly buried but which was able to taste paradise as forbidden fruit.

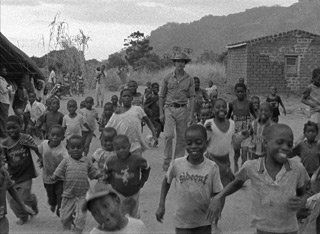

A number of viewers may be shocked by the title of the second part of the film, 'Paradise', in that this very romantic and very melancholic love story takes place in the setting of a Portuguese colony in Africa[2], soon shaken by the unrest of the war of independence. In particular, we see settlers practising arms drills even though the two lovers, the main characters in this story, do not take part in this training and seem to be secretly detached from that universe.

While the camera shows black people reduced to the level of mere servants or farm workers exploited in the hillside fields, it is difficult to imagine that the paradise in question could have meant anything other than the private world of white people.

While Portugal is today a European country with only 10 million inhabitants, it was also the originator, from the end of the 15th century, of what the history books still call the Great Discoveries. This era of exploration of the world by brave navigators is still, for Portugal but also for Europe, synonymous with the epic - an epic celebrated in particular by Luis de Camõens in his famous Lusiades, published in 1572.  Certainly, this glorious image of heroism has been questioned many times, particularly because of long colonial wars fought in Africa by the dictatorial Salazar regime, then by the profound changes in Portuguese society following the 1975 Carnation Revolution which established a democratic regime and paved the way for the country joining the European Union. However, this past remains ambivalent, more or less conflicting, more or less hidden but still present.

Certainly, this glorious image of heroism has been questioned many times, particularly because of long colonial wars fought in Africa by the dictatorial Salazar regime, then by the profound changes in Portuguese society following the 1975 Carnation Revolution which established a democratic regime and paved the way for the country joining the European Union. However, this past remains ambivalent, more or less conflicting, more or less hidden but still present.

The prologue of Tabu thus reproduces the most conventional imagery of colonial exploration in Africa with this adventurer who, accompanied by a few black porters, disappears alone into the hostile jungle, even though the director's irony is clear and emphasises the whole unreality of the sequence. More significantly, the narrator's voice-over reveals that the character is not motivated in his expedition by the official reasons of colonial endeavour, such as the glory of god or the empire, but by a gnawing heartache that eventually drives him to an almost ridiculous suicide. The white man in the cinema thus appears detached from his own actions which, 'in reality', are part of the whole enterprise of African colonisation with all its violence and brutality.

It is the same detachment that we find in the second part of the film, 'Paradise', where the two main characters become increasingly isolated in their illicit passion. However, more broadly, we note that only the settlers seem to have significant motivations like love, jealousy, friendship and remorse, while the black people are reduced to the role of merely obedient extras. Less explicitly than in the prologue but noticeably nonetheless, the setting reveals, thanks in particular to the detachment of the voice-over, the illusion in which the characters live, their indifference to the real world around them and their isolation in a largely imaginary universe.

It is the same detachment that we find in the second part of the film, 'Paradise', where the two main characters become increasingly isolated in their illicit passion. However, more broadly, we note that only the settlers seem to have significant motivations like love, jealousy, friendship and remorse, while the black people are reduced to the role of merely obedient extras. Less explicitly than in the prologue but noticeably nonetheless, the setting reveals, thanks in particular to the detachment of the voice-over, the illusion in which the characters live, their indifference to the real world around them and their isolation in a largely imaginary universe.

In the same context, how can we not laugh at Gian Luca Ventura's orchestra playing, in all sincerity, a global hit with words as romantic as they are conventional, while the country is being turned upside down by a long and violent war?

The same consideration of about the colonial representation in Tabu leads us to question the first, apparently more realistic, part of the film, which is the time of a 'Paradise lost'. The relations between old Aurora and her servant or carer, Santa, are brought to the fore. Several contrasting traits between these two characters can thus be easily seen: one is now very elderly, suffering from dementia, having once had a sizeable fortune which is now largely squandered - as shown by the fur coat that she is preparing to pawn; the other is younger, without great financial means, perhaps having recently arrived in the country - she learns how to write by reading a Portuguese version of Robinson Crusoe, while this famous novel by Daniel Defoe illustrates, as we are well aware, the superiority of the white man over 'indigenous' people, in the image of Friday who became the devoted servant of his master Robinson. We can see a relationship of control, even though it is in the form of the relationship between master and servant.

However, the distance between people seems just as great as somewhat indirectly shown by the 'madness' of Aurora, who believes she is being persecuted by her carer, whom she does not hesitate to treat as a monster or a witch - we recall the second part of the film, in which young Aurora dismisses a slightly mystical cook who, in addition to her pregnancy, had predicted a lonely and bitter end for her.

The world of individuals seems just as isolated, and we know nothing of Santa's real feelings. She seems just as impenetrable as the black people were in colonial times, mere extras in the second part of the film. While Pilar tries to convince her to care for Aurora better, Santa replies by saying she is an obedient servant who only answers to the old woman's daughter (who probably pays her salary).

Some viewers will undoubtedly find such an interpretation forced and will note that the colonial situation is only barely evoked in the film as a faintly sketched setting. Miguel Gomes's film does not restrict itself merely to illustrating a thesis, even metaphorically. Its aesthetic aspect, which is establishes in particular the visible contrast between its two main parts, should therefore be better considered.

Those viewers who are least aware of the cinematographic aesthetic will note several very obvious features of Tabu such as the use of black and white or a relatively narrow aspect ratio (1.37:1)[3], which is now unusual in cinema. Cinema enthusiasts will surely recall that Manuel Gomes's film has the same title as a great classic, the last film by Friedrich Murnau, which dates from 1931 and consists of two main parts: 'Paradise' and 'Paradise lost' (in the English version), so identical to Gomes's film but the other way round. Furthermore, as the title suggests, Murnau's silent film also tells the story of a forbidden love, although the setting is very different since the action takes place on the island of Bora Bora in Polynesia. Several images from Gomes's film seem to be directly inspired by, if not pastiches of, its predecessor, such as the brief shot where we see Gian Luca blow into a conch, an image repeated several times by Murnau, or even the Super 8 film shot by Aurora's husband beside a waterfall, which cannot fail to recall one of the first sequences of the original Tabu where the two lovers meet for the first time beside a similar waterfall.

The style of Gomes's film - particularly when we consider the prologue and the second part - has less in common with that of the German film-maker than with classic Hollywood films supposed to take place in Africa. The most distinctive characteristic of the two African episodes is certainly the absence of audible dialogue, a very unusual process that clearly harks back to the silent era of cinema. In reality, the soundtrack of Gomes's film is very elaborate. If we pay attention, we can hear that the dialogue is essentially 'faded', while some of the ambient sounds and the accompanying music are clearly there! Furthermore, old Gian Luca's voice-over, as well as old Aurora's as she reads the letters from her youth, can also be heard and play a vital role in helping us to understand the story.

This approach is original enough to be easily noticed by all viewers - for example, we hear the sound of the gunshot fired by Aurora but no sound of the row between the two men that precedes it. The director is skilful enough, particularly in using voice-overs, to avoid the process being perceived as completely artificial. As the second part is presented as a memory remembered in images, the absence of dialogue will be perceived by most viewers as a sign of the reconstituted nature of these images. The references to silent film, the 'art of the past', will reinforce this impression even though the events shown take place much later, most likely in the 1960s, judging by the characters' clothing and the musical references.

This approach is original enough to be easily noticed by all viewers - for example, we hear the sound of the gunshot fired by Aurora but no sound of the row between the two men that precedes it. The director is skilful enough, particularly in using voice-overs, to avoid the process being perceived as completely artificial. As the second part is presented as a memory remembered in images, the absence of dialogue will be perceived by most viewers as a sign of the reconstituted nature of these images. The references to silent film, the 'art of the past', will reinforce this impression even though the events shown take place much later, most likely in the 1960s, judging by the characters' clothing and the musical references.

We also note various, more ironic features that encourage viewers to take a step back to consider the characters and events. This is particularly the case in the prologue, where the bombastic words of the narrator (who, for example, calls the explorer a 'melancholy creature'), the posture of the character literally overcome with pain, the piano music with slightly mechanical notes, and the almost absurd role played by the crocodile, which becomes an instrument of suicide, convey a spirit of mockery, if not black humour, that marks the whole sequence.

The irony is less evident in the second part of film, which is has a melancholic tone imparted by Gian Luca's sombre voice. However, at several points we see hints of mockery with regard to the characters on screen. For example, when the two lovers are separated, their tear-stained faces with the excerpt of 'Be My Baby' playing seem close to caricature, although their emotion can be clearly shared. Some attitudes such as the Aurora's determined walk in the bush, with a gun in her hand, the murder of Gian Luca's friend by Aurora (the camera switching 90 ° as if taking the point of view of the dead person) or even the husband slapping the lover who has just been thrown to the ground in the dust may seem artificial, almost comical. Movements similar to those of classic American silent film can also be recognised here. Finally, there are sometimes barely perceptible details like the photo session of the musical group perched in the tree, a session that lasts a little too long, or Aurora's involuntarily obscene gesture when she spreads her hands apart to show the supposed size of the disappeared crocodile, or even the crocodile's name, Dandy, a supposedly romantic name according to Gian Luca but which today is a comical reminder of the famous Australian film Crocodile Dundee.[5] The whole story of the little crocodile, which repeats that of the prologue in an unconventional way, appears to be a kind of MacGuffin, a red herring intended to maliciously mislead the viewer.

The work on the soundtrack and the favoured use of voice-overs, the traces of more or less subtle irony as well as the diverse but obvious cinematographic references certainly help make the whole second part 'unreal', forcing the viewer to take a step back from the events shown on screen. It thus remains to examine the direction in the first part of the film, which is seemingly dealt with in a more realistic manner.

At first glance, the aesthetic of the first part does not seem to be very striking, immersed in the rainy greyness of the winter months, while the space seems narrow, the characters being confined to their apartments, filmed most often in medium shots (which contrast with the many long shots in the second part, often open shots on broad landscapes). The editing of these different sequences is also significant, each of them being presented in a discontinuous, almost disjointed, way, like an unfinished sketch. Thus, after going to look for Aurora in the Estoril casino and after hearing her describe her dreams without interrupting or reacting, Pilar finds herself in her apartment, plunged into darkness while the sound of heavy rain can be heard outside; there is the muffled sound of a mobile phone ringing, intriguing Pilar who, after some hesitation, discovers the device in the refrigerator!

The links between the different sequences are therefore tenuous, often problematic, as the events are cut in a way that may appear random or arbitrary, leaving the feeling of events on hold. This fragmented, inconclusive, uncertain reality contrasts with the classical aspect of the story of the second part, in which events are linked equally quickly and coherently. 'Paradise lost' thus appears as a world threatened by insignificance and absurdity, of which Aurora's 'madness' is only an exaggerated form. However, more specifically because this madness is only seemingly real and it is the trace of a buried history that is not perceived by the other protagonists, the image-based fiction in the second part of the film appears perhaps to be more 'real', aesthetically, and certainly more intense than this grey and mundane reality.

The links between the different sequences are therefore tenuous, often problematic, as the events are cut in a way that may appear random or arbitrary, leaving the feeling of events on hold. This fragmented, inconclusive, uncertain reality contrasts with the classical aspect of the story of the second part, in which events are linked equally quickly and coherently. 'Paradise lost' thus appears as a world threatened by insignificance and absurdity, of which Aurora's 'madness' is only an exaggerated form. However, more specifically because this madness is only seemingly real and it is the trace of a buried history that is not perceived by the other protagonists, the image-based fiction in the second part of the film appears perhaps to be more 'real', aesthetically, and certainly more intense than this grey and mundane reality.

However, it is certainly up to each viewer to make that choice, to decide whether the paradise of a cinematographic passion is worth more than the prose of everyday life. Without prejudging everyone's opinion, you will notice that the second part of the film, which seems to imitate classic Hollywood cinema, as mentioned, includes at least one scene that would have been impossible in that genre of films (because of the prudish standards of the Hays Code), and which illustrates the physical love uniting Aurora and Gian Luca. This scene, underscored by the sombre voice of Gian Luca, who explains how much this passion transformed him, is dealt with frankly, without irony or any other form of detachment, and culminates in the young woman looking to camera, thus directly questioning the viewer. Perhaps here we see here the film-maker's preference for the intensity of a lost love, even though he emphasises several times the irreducible role of fiction in this cinematographic reconstruction.

6. Questions or situations for discussing the film

|

1. any viewers do not remember these words (though it is not the mention of the crocodile) and consequently believe that the name Ventura only appears when Aurora spells it out with her fingertips on Santa's palm (who then copies it on a piece of paper that she gives to Pilar). However, lying on a stretcher, Aurora talks of Gian Luca then of Ventura, without it being understood whether it is the same person or if the crocodile actually existed.

2. The film was shot in Mozambique, a former Portuguese colony, which has been independent since 1975 after a long war, which began in 1962. The Mount Tabu that is mentioned in the film does not exist and Mozambique is not referred to as such.

3. This is the ratio between the width and the height of the image: the 1.37:1 (or 4:3) aspect ratio therefore refers to a relatively square image, while since the end of the 1950s, mainly to deal with competition from television, cinema has preferred a wider image (1.66:1 or 1.85:1), or even very a wide image such as CinemaScope (2.66:1).

4. The first name of Miguel Gomes's heroine perhaps also alludes to another famous film by Murnau, Sunrise (1927), which translates into Portuguese as Aurora.

5. Christophe Beney noted it.